April 4, 2018

Here are highlights of our 87 pages of public reply comments. Read the full comments at the PRC website here.

- The initial comments confirm that the proposed above-CPI rate increases are fundamentally arbitrary.

- Despite the commenters’ disparate conceptions of an ideal ratemaking system, the most striking feature of the initial comments is their near unanimity that the proposals offered by the Commission would not comply with the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act of 2006 (PAEA), are not a reasoned solution to the problems found by the Commission and would not withstand judicial review.

- The Commission’s proposal cannot withstand appellate review because there is no principled basis for the additional rate increases that the PRC would allow the Postal Service to impose on captive mailers.

- The failure to prove a causal link between the regulatory system and the Postal Service’s alleged revenue inadequacy is fatal to all of the proposals in this docket for above-CPI rate increases.

- The proponents of above-CPI rate increases ignore the risk that they will cause a large enough decline in volume to be self-defeating.

- The Commission may believe that mailers are overstating the effect of these price increases. But the Commission, unlike EMA, Idealliance, ACMA or IWCO Direct, has performed no analysis whatsoever of the effect on volume of CPI+2, 3, 5, or any other increase, and therefore has no data suggesting the opposite.

- The Postal Service tries to finesse this problem by disclaiming any intention to raise prices to a level that drives enough mail from the system to become counterproductive.

- But the Postal Service’s barrage of attacks on the Commission’s proposals as inadequate implies that the Postal Service would implement rate increases exceeding CPI+5.

- The Postal Service cannot have it both ways. Either the Postal Service is bluffing when it claims that the rate increases contemplated by the Commission are inadequate, or the Postal Service intends to raise its rates as much as the Commission allows.

- The comments of the postal labor organizations are in the same vein. On the one hand, the unions contend that the above-CPI surcharges proposed by the Commission are grossly inadequate. Yet a union simultaneously insists that, “because of market constraints and competitive forces that apply to all USPS products, the grant of additional pricing flexibility will not lead to unnecessary or unwarranted price increases.” Another union says, “The Postal Service will not pursue suicidal rate increases.”

- In short, the Postal Service desperately needs massive rate increases, but can be trusted not to impose them even if permitted.

- The Public Representative has at least tried to predict the volume effects of the CPI+2 proposal by extrapolating from existing elasticity estimates. But as ANM et al. and NPPC discussed in their initial comments, predictions drawn from these elasticity estimates are unreliable because the Commission is proposing to allow rate increases that exceed CPI to an extent far greater than has ever occurred since the enactment of PAEA. All available elasticity estimates have been developed during a period of essentially no real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) price changes.

- The above-CPI rate increases proposed are unjustified by the Postal Service revenue needs.

- The initial comments of the Alliance and its allies showed that the analysis of Objective 5 (revenue adequacy) by the PRC is flawed in two respects. First, the Commission has improperly elevated Objective 5 over all other statutory objectives: Section 3622(b) requires that Objective 5 be considered in tandem with the other objectives. Second, the Postal Service’s revenue needs could not justify the rate surcharges proposed by the Commission even if (contrary to fact) revenue adequacy were the sole or paramount statutory objective.

- The Postal Service has achieved short-run financial stability.

- The Postal Service’s “default” on its nominal prefunding obligations to the Treasury does not impair in any way the Postal Service’s ability to actually meet underlying obligations to current or future retirees. Moreover, the Federal Government has informally forgiven the accelerated prefunding obligations. The Postal Service has “not incurred any penalties or negative financial consequences as a result of not making the PSRHBF prefunding payments”; does not “anticipate any legal consequences, under current law, from its inability to make the required payments”; and “expects” that “additional legislation will be enacted to address the short-term funding requirements” of the Postal Service and “address regulatory restrictions that have not allowed the Postal Service to adjust its operations to levels commensurate with its current revenue base.” USPS Form 10-K for FY 2017 at 5 & 43.6 One might ask whether the failure to make these payments represents a “default” at all.

- As for capital investments, there is no evidence that the Postal Service has a backlog of capital investment projects that have been foregone for lack of funding. We discuss this issue in more depth below. For now, it is enough to note the complete absence of any evidence on the record that the Postal Service has deferred investments “that are critical to [its] near-term continued operation.”

- The Postal Service nevertheless insists that the concept of short-term financial stability should play no role in the Commission’s analysis because “objective 5 clearly inheres an expectation that the Postal Service must cover its costs.” “Otherwise, it could not generate retained earnings, and that statutory phrase would be surplusage.” This reasoning is inscrutable. Regardless of what costs the Postal Service must cover to remain profitable, the fact that the Postal Service might not generate retained earnings does not render the statutory language surplusage. As NPPC explains, “Congress included the term ‘retained earnings’ in the PAEA to make clear that the ‘breakeven’ requirement in the former law was no more.” PAEA did not guarantee the Postal Service retained earnings. It simply permitted them. As ANM et al. explained in their initial comments, this change was made not to ensure that the Postal Service would cover its costs, but to incentivize it to reduce them.

- And whatever the meaning of “financial stability” under Objective 5, the Commission cannot design a system that would allow the Postal Service to recover more of its costs than the market will allow. The Postal Service is saddled with obligations that a private sector business would not be, including retiree benefit prefunding requirements. These obligations will necessarily limit the Postal Service’s profitability. There is a limit to how much even an unregulated monopoly can charge for its services.

- The Postal Service calls its “defaulted” prefunding obligations “past-due but thus-far uncalled debts to the U.S. Treasury.” But the Postal Service knows that there is essentially no risk that these debts will be “called.” The Congress and the U.S. Treasury are not going to put the Postal Service out of business. The very idea is absurd— even if Treasury did call these debts, someone would deliver the mail.

- The longer-run loss projections of the proponents of above-CPI rate increases are unsupported.

- The claims of the Postal Service, its allies, and the Public Representative concerning the Postal Service’s medium- and long-run financial prospects are also flawed.

- These commenters (1) ignore the increasing contribution of competitive products; (2) ignore the expected benefits of total factor productivity growth; (3) ignore the ability of the USPS to cover “exogenous costs” in FY 2017 if the USPS had not let its productivity growth collapse after the implementation of the exigent surcharges; and (4) overstate the effect of delivery point growth on costs.

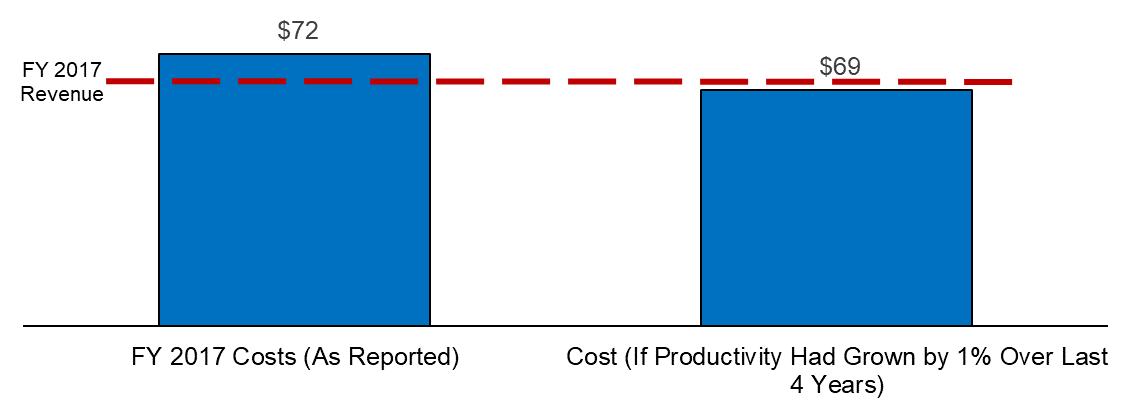

- The Postal Service’s losses in FY 2017 were due entirely to the collapse of Postal Service productivity growth since Fiscal Year 2014, when the exigency surcharge took effect. As we noted in our initial comments, if productivity had risen by just one percent annually from FY 2014 to FY 2017 (as it previously had), the $2.7 billion loss experienced in FY 2017 would have been a small surplus.

- Furthermore, after adjusting for changes in mail mix, the unit attributable costs of market dominant mail in FY 2017 were actually higher in inflation adjusted dollars than in FY 2008.

Collapse of USPS Productivity FY 2014-2017

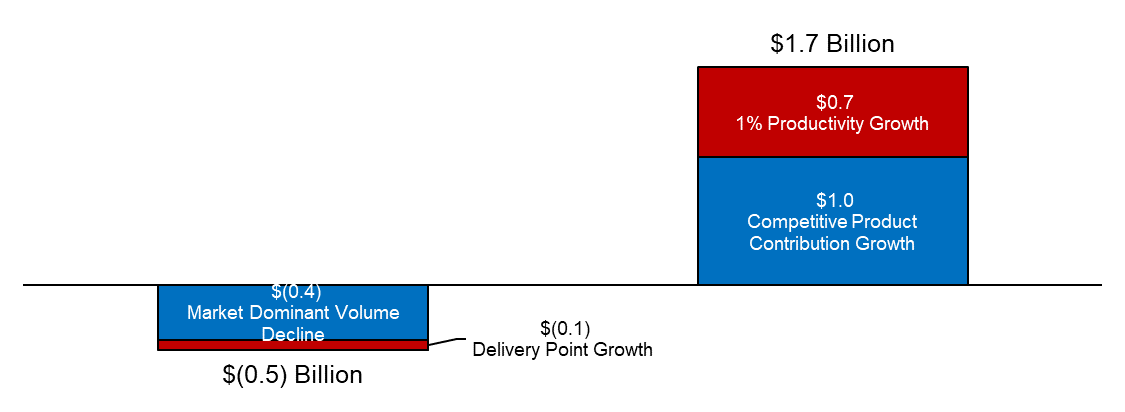

- The financial “headwinds” projected by the USPS and the Public Representative are far smaller than the financial tailwinds that the same parties ignore.

- Market dominant volume declines and delivery point growth reduce the Postal Service’s net contribution by about $500 million each year (about $400 million per year from the decline in market-dominant volume, and about $75 million per year from the increasing number of delivery points). But the tailwinds from the ongoing growth in contribution from competitive products (about $1 billion per year) and the growth in total factor productivity that the Postal Service has shown it can achieve when given proper incentives (about one percent or $700 million per year) are more than three times the magnitude of the headwinds.

USPS Annual Headwinds Much Smaller than Tailwinds

- The Postal Service’s own financial projections confirm that it would earn a healthy profit by taking advantage of readily available revenue sources and available cost savings.

- As ill-documented as USPS Appendix A is, it nonetheless amounts to a powerful if inadvertent admission by the Postal Service. The appendix confirms the hollowness of the Postal Service’s claimed need for steeper rate increases on market-dominant mail products. A valid estimate of the Postal Service’s legitimate financial needs must reflect its actual projected growth in revenue and reasonable assumptions about the productivity growth and cost control that the USPS could reasonably achieve. Modifying a few of the stated assumptions of Appendix A in this direction, while leaving the other values and assumptions underlying the appendix unchanged, transforms the Postal Service’s projected financial results during the period at issue from the losses projected in the appendix to healthy profits. Because the Postal Service has filed both the appendix and the “workpapers” ostensibly supporting it as nonpublic documents, we cannot disclose our analysis or results here. But they are set forth in nonpublic Appendix B, infra. We urge the Commission to review it.

- The proposed across-the-board surcharges would devastate the Postal Service’s incentives for efficiency.

- Not only are the above-CPI surcharges unnecessary to resolve “baseline losses” and establish financial stability, but the potential for extra revenue from the above-CPI rate increases proposed by the PRC would eviscerate the Postal Service’s incentives to control its costs and improve its productivity. Nothing in the Commission’s proposal would require the Postal Service to invest any of its additional revenue on productivity improvements. Far from triggering a “harmonious cycle,” the rate increases would have the opposite effect. This fact is confirmed by the collapse of the Postal Service’s productivity growth since the effective date of the exigency surcharge in Fiscal Year 2014 and the slackening of productivity growth experienced by several foreign postal operators since the recent relaxation of price cap regulation abroad.

- The record does not support the Postal Service’s claim that insufficient investment capital is the main reason for the Postal Service’s poor productivity and cost control.

- The Postal Service fails to identify any investment capable of materially reducing its costs that has been canceled or delayed by a lack of funds. The only delayed capital investment that has been identified on the record relates to upgrading the Postal Service’s vehicle fleet. As we have noted, the Postal Service has plenty of money for new vehicles.

- Moreover, the insufficient-investment-capital theory ignores the decline in the Postal Service’s volume and workload in recent years. It would make no sense for USPS to invest as much (or as high of a percent of revenue) in a declining volume environment as the USPS invested in a growing volume environment.

- The Postal Service has ignored its ability to raise the funds for new assets by selling assets that are no longer needed.

- The Postal Service and its allies have ignored the major cost savings that the it could achieve without major new investment spending.

- In reality, it should be unnecessary to evaluate exactly how much additional capital the Postal Service needs or how it intends to spend that capital. The price cap itself is designed to provide the proper incentives for the Postal Service to make sound decisions about how to spend its capital. Admittedly, the results to date have not always been encouraging. The FSS debacle is a glaring example of misguided, and costly, capital investment that has reduced

- But the price cap does not just provide incentives to invest in efficiency enhancing capital improvements. It also provides incentives to cut costs and increase efficiency in other ways. That is the beauty of a price cap—it provides incentives to reduce costs and increase efficiency, but it is agnostic as to how those improvements are achieved. The Postal Service and the Commission, however, are not so irreligious. They have acted like acolytes at the altar of capital expenditures.

- The Postal Service refuses to acknowledge these options, however. Rather, it insists that all declines in efficiency result from declining capital investment, that only by increasing capital investment can the Postal Service improve efficiency, and that the only hope for financial stability lies in massive rate increases for captive mailers. This mindset is precisely the kind of passive and unimaginative thinking that incentive ratemaking is designed to prevent.

- The Postal Service’s comments inadvertently expose the fundamental illogic of the Commission’s “harmonious cycle” theory.

- The Postal Service insists that “in the market environment that has prevailed for the last two decades, the Postal Service has strong inherent efficiency incentives.” It argues that “the best thing that the rate regulation system can do is to give the Postal Service the flexibility to make capital investments and other business decisions necessary to fulfill its universal service mission in an efficient and effective manner.” (In plain English: give us the captive mailers’ money and leave us alone.)

- This position is curious. Whether the Postal Service’s incentives to reduce costs and increase efficiency are “inherent” or not, the Postal Service seems to believe that the incentives are maximized under the current ratemaking system. And if these incentives are unrelated to the ratemaking system, it would seem that changing the system would not maximize them further. Like the Commission, it fails to tie the incentives provided (or not) by the ratemaking system to the changes it would propose to that system.

- The Postal Service’s logic would be impeccable if there were any factual support for the premise that the Postal Service cannot increase operational efficiency without additional revenue. As explained above, however, its current inefficiency is not the result of a lack of capital, and its future efficiency growth is not dependent on additional capital. In fact, the Postal Service itself contradicts this premise with its repeated assertions that it has limited remaining opportunities to reduce costs or increase efficiency. If the Postal Service is already operating as leanly as possible, how will additional revenue improve its efficiency? What would it use the funds for?

- If the Commission is unconcerned with the Postal Service’s abuse of its market power, unconcerned with volume losses in response to increased prices, and confident that additional revenue will be used solely to improve operational efficiency and service performance, then the Commission should simply let the Postal Service charge whatever it wants, no questions asked.

- The Postal Service’s proposals would make it an unregulated monopoly.

- The Postal Service exposes its agenda when it states that it “remains deeply skeptical of any price cap’s ability to achieve the statutory objectives in light of the statutory factors.” The Postal Service has never accepted the price cap as a legitimate form of regulation, despite its widespread acceptance in economic literature, and accordingly has never operated as if it would be forced to abide by the cap if it suffered losses. The Postal Service seems at times to have spent more effort over the past ten years asking Congress and the Commission to loosen the price cap than evaluating the Postal Service’s operations, management structure, and business philosophy to develop a strategy for success within the cap.

- The Postal Service’s initial comments reflect the same oppositional mindset. As discussed above, the Postal Service absurdly contends that it has exhausted all the potential efficiency improvements that may have once existed and is now condemned to a future of inexorably rising costs and declining volumes. The only solution to its overstated woes is a constant injection of more revenue—not in exchange for better service or improved product offerings, but unconditionally. This defeatist assessment of its financial condition is coupled with legal arguments that are similarly focused on achieving one goal: more revenue, without conditions. This exclusive focus on obtaining more revenue manifests in arguments that are inconsistent and self-contradictory. But more fundamentally, the result the Postal Service seeks is incompatible with its status as a monopoly service provider under PAEA.

- The Postal Service is a monopoly and must be subject to stringent rate regulation.

- The plain text and structure of PAEA require the Commission to protect mailers against the Postal Service’s abuse of this monopoly power. PAEA established two kinds of products—market dominant and competitive. It defined market dominant products as “each product in the sale of which the Postal Service exercises sufficient market power that it can effectively set the price of such product substantially above costs, raise prices significantly, decrease quality, or decrease output, without risk of losing a significant level of business to other firms offering similar products.” A product over which the Postal Service has market dominance is subject to maximum rate regulation. A product over which the Postal Service lacks market dominance is not.

- In any event, the performance of Royal Mail and several other foreign postal operators since the abandonment of price cap regulation in the United Kingdom is a chilling lesson about what would lie in store for mailers in the United States if the Commission were to follow the British lead: massive above-inflation rate increases for captive mailers, and a collapse of efforts to control costs and improve productivity. That prices may have increased more slowly after the initial surge is no solace. This pattern is exactly what one would expect from a deregulated monopoly—an immediate increase in prices to raise them to the profit maximizing monopoly level, then a subsequent leveling as increases above this level would lessen profits. Monopoly power does not involve the ability to increase prices without limit. Even a pure monopoly has a profit-maximizing price above which profits fall off. But the monopoly can raise prices above what would exist in a competitive market at the expense of captive consumers. Royal Mail did just that, and the Postal Service wants to follow suit.

- Additional surcharges for Periodicals and Marketing Mail Flats are also unwarranted.

- The failure of Periodicals Mail and Marketing Mail Flats to cover attributable costs is a cost-control problem, not a revenue problem. These products lose money because of a series of Postal Service management bungles: (1) failing to scale down its operations in response to declines in mail volume; (2) making and then doubling down on a misguided investment in the FSS; (3) deliberately mispricing Carrier Route Basic flats; and (4) failing to address the Postal Service’s longstanding personnel compensation issues. Eliminating the first two of these unforced errors would allow flats to become fully compensatory, or nearly so—even without considering the related contribution from First-Class Mail, letter-shaped Marketing Mail and package volumes that periodicals and catalogs generate.

- The Commission’s meat-axe approach to “non-compensatory” mail products in the present docket also contrasts with the far more balanced approach of the surcharges proposed in the 21st Century Postal Service Act of 2012 (S. 1789) and the Postal Reform Act of 2013 (H.R. 2748). The Commission’s approach is also at odds with the approach taken in S. 2969, the Postal Service Reform Act of 2018, a bill introduced by a bipartisan group of Senators on March 22, 2018. Section 202(c) of the bill would authorize the Commission to impose above-CPI increases on “underwater” products in certain circumstances. But the remedy proposed by the bill is far more balanced than the one-dimensional approach of the PRC order. Section 202(c) would require the Commission, before imposing any surcharge on “underwater” products, to “determine whether any operational decisions of the Postal Service have caused any direct or indirect costs to be inappropriately attributed to any underwater product”; quantify the impact of any such operational decision”; and net out any costs so inflated or inappropriately attributed before imposing any surcharge on “underwater” products

- Conclusion

- The initial comments reveal a striking industry consensus that the alternative regulatory system proposed in Order No. 4258 should not be adopted. For the reasons explained above, the proposed system is fundamentally arbitrary and inconsistent with PAEA. Even the comments that advocate greater rate surcharges than proposed in Order No. 4258 underscore the basic flaws in the Commission’s approach.

- Second, there is no immediate crisis that requires immediate adoption of final rules. As the Commission found in Order No. 4257—and the Postal Service acknowledged in its most recent Form 10-K—the Postal Service has sufficient funds to continue providing mail service in the short run and for the foreseeable future. The Commission has time to pull back and rework its proposals.

- Moreover, for the reasons discussed above, the proposals would need to be revamped so thoroughly to meet the requirements of reasoned decision making under PAEA that the Commission could not prudently adopt final rules without further comment from interested parties.

- Finally, there is another reason why the Commission should avoid rushing out a final rule. That reason resides at the eastern end of Pennsylvania Avenue. Two recently introduced postal reform bills, H.R. 756 and S. 2629, reflect a growing recognition in Congress that comprehensive postal reform must deal with issues that are beyond the Commission’s control, and therefore requires legislation.

- The pendency of the Senate and House bills underscores what the record in this case should independently make clear. The Commission should not— and need not—issue final rules in this docket before remedying the deficiencies in the current proposal. A rush to judgment would benefit neither mailers nor the Postal Service. Rather, the Commission should work jointly with Congress, the mailers and the Postal Service to seek the comprehensive solution that a solo Commission effort cannot produce.

Leave a Reply